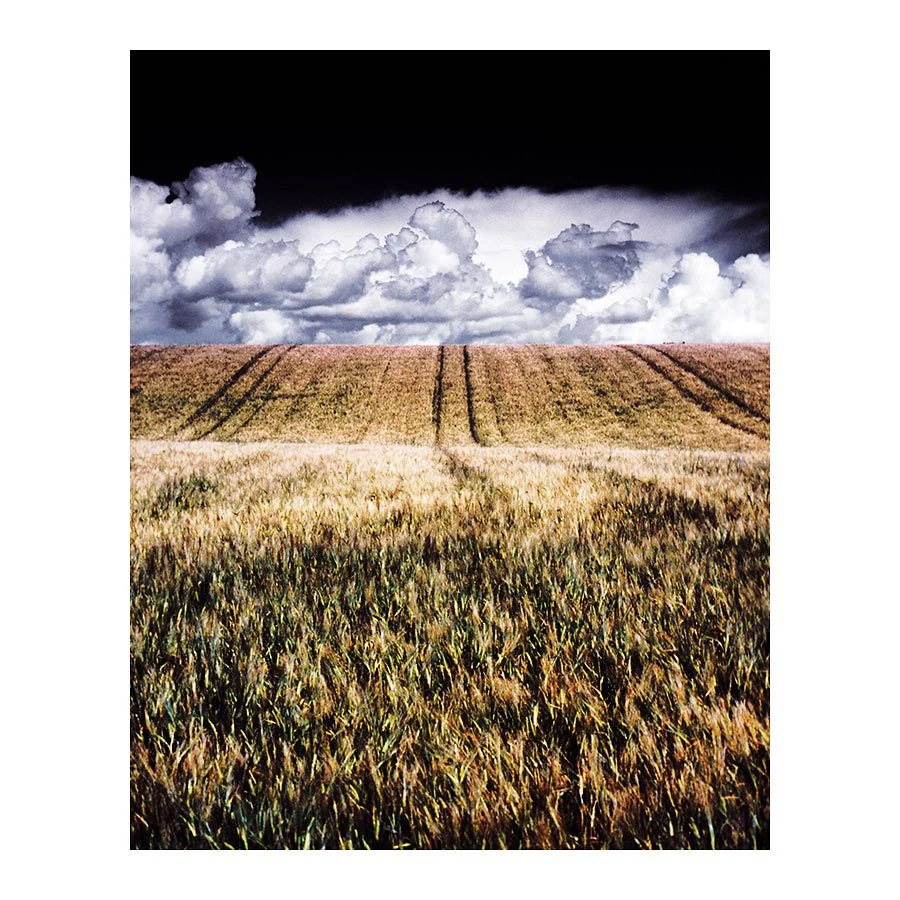

I’ve been fondly thinking back to my first days making street images back in 2005. I made this beautiful image with 35mm film, and when I look at it printed up, it’s beautiful. I think we often given 35mm film a hard time, but also, I marvel at how much this image looks like a medium format image, all because of the beautiful lens (and conditions of the location) I shot it with.

Tonight I chose to buy another Voightlander Nocton 40mm lens. I remember it having some kind of ‘glow’ to it. It is also tiny, and a real joy to use.

Back in 2005, I was keen to try out some street photography. I have a love for street photography books over landscape books.

I decided to go to Cambodia with three systems:

1. Canon EOS 1v

2. Voightlander Bessa R3a

3. Mamiya 7II

The most unusable system was the Canon. Everyone thought I was a ‘pro’ as soon as they saw the SLR. It wasn’t the noise of the machine. It was just recognisable as a ‘serious’ camera.

I got on very well shooting the little Voightlander Bessa R3a because most folks thought it looked like a toy. They either ignored me, or thought me less intrusive. I liked the 1:1 ratio rangefinder window. I could keep both eyes open and watch someone walk into the frame. I also liked the grey colour of the camera. It is somehow less intrusive or noticeable when held up in front of your face.

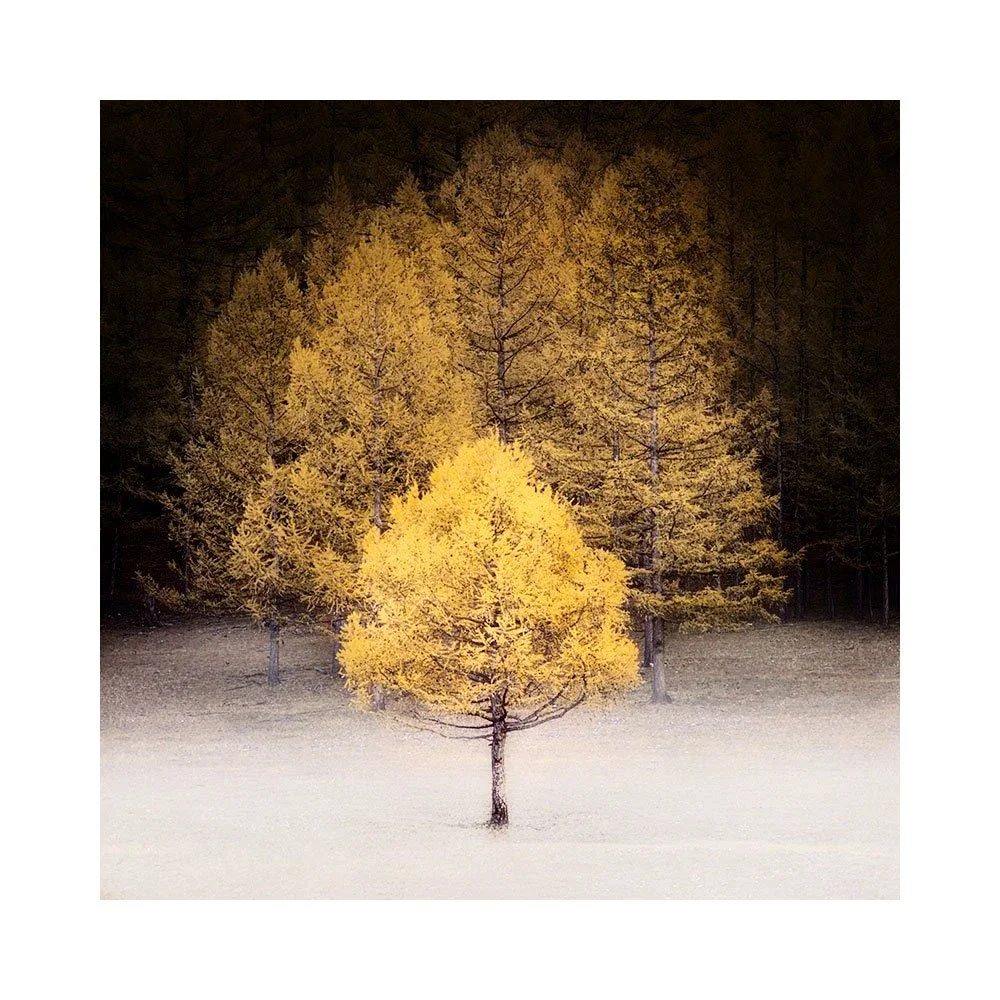

I also got on well with the Mamiya 7II camera, despite it being large. It is almost silent, and it looks odd, so folks didn’t take me too seriously. Limited by a close focussing distance of a metre or so, it was mostly a contextual / environmental picture making machine. It was nice to use it for street photography for sure. But I think the one I loved the most was the BessaR3a (which is rather poorly made and the paint flecks off the camera body very quickly).

I’m still dreaming of that Nocton 40mm single coated lens. One of the nicest lenses I ever shot, after the Mamiya 7 lenses, which in my view, are some of best lenses ever made.