Haven’t heard about Ivermechtin yet? Why not?

Hearing Loss and how it tells us something about visual perception

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Sometimes in order to explain something we use a comparison. So today I’d like to discuss hearing and how our perception of sound is due to a lot of unaware processing that goes on. This I think is a good way of drawing a comparison to the limitations of our vision.

It is my belief that most photographers assume that their pictures aren’t good because they just need to practice more (this is sort of true to a point), but there are serious limitations to our vision that once we understand this, things will never be the same again for us.

So let’s talk about hearing today.

In Bella Bathurst’s book about Sound, she describes many of the psychoacoustic issues surrounding hearing.

When fitted with a hearing aid for the first time, many hearing-loss sufferers tend to find them too loud. We just trust that what we hear, is a true representation of the sounds around us. But this is not so and in the case of someone with hearing loss, an adaption has happened. They have become habituated to the lower levels of auditory experience. When normal volume levels are reinstated, they find them overwhelming.

Our brain processes the sound we hear, and our ‘auditory processing’ filters a lot of unwanted sound out for us. For instance, when in a loud environment such as a motorway, we are often able to still pick out the words someone is speaking to us over the rumble of background traffic. In its truest form, the sounds may be a lot louder and yet our experience of them is quite different.

When someone who has suffered hearing loss is given aids, it takes months for their brain to ‘adapt’ to processing the new sound. Loud environments may be very difficult because to the patient, everything seems at the same level for a while. Voices are no longer over background traffic. Instead the traffic noise is not a background noise. It is just as forward in experience as someone talking is. The brain needs time to ‘learn to hear’ again.

Should the patient continue to use the aids for a long time, things settle down. Their auditory processing ‘learns’ to separate out sounds from each other, and also to filter out, or place in the background the sounds it knows aren’t important.

This is the key point: our hearing innately filters out what is not needed. This is a fundamental function of hearing for all of us. We do not hear what is there, we hear a highly filtered, processed version of the sounds around us.

The same is true for vision. Our brains take in the visual information and ‘construct’ a representation of what is happening around is. What was before our eye, and what we experiences are never the same.

We ‘construct’ what we see. It happens so quickly that we aren’t even aware of doing it. This is why I have discussed the necker cube before, as this wire frame cube allows us to experience the ‘construction’ first hand.

Let’s consider the cube then. We all see this cube right?

Of course there is no cube there. It is only white lines on a black background. But we have ‘constructed’ a cube in our minds.

This is the first level of abstraction that is happening innately. But even this description of what we are seeing isn’t entirely accurate either. Not only does the cube not exist, but neither do the white lines and black background. In truth we are staring at a bunch of black and white pixels.

To experience the construction of the cube in our mind’s eye, we can do this by forcing the front and back walls of the cube to invert. What we perceived as the front wall of the cube is now the back wall, and what was the back wall is now the front wall. Try it - stare at the cube and imagine which wall is the back wall and then flip it.

If you’re still not with me about this, then consider the four drawings below. All are cubes. The top two are the hardest to ‘see’. With these harder to ‘see’ cubes, if you work at them, you’ll eventually ‘see’ them. Except you’re not ‘seeing’ them. You are ‘constructing’ them. This is ‘visual construction’ at play:

This allows you to experience the construction that is an innate part of your vision. This ‘construction’ is happening all the time, without you knowing it and it is a reminder to me that what I am seeing is really a processed version. This I find quite interesting because it leads me down a rabbit hole of ‘what is reality’ if we can’t entirely trust our senses?

As we all know, cameras do not see the way we see. They see a 2D representation of what we call ‘reality’, and they also record tone very differently. Whereas we see a compression of tone (and thus do not require ND grads to control sky tones), the Camera does not compress tone. So we have to use grad filters on the camera to compress the tonal range entering the camera.

I find this all very fascinating. What we see, and what is really there are two separate things. Our senses are highly adaptable. They cannot be trusted to show us what is there, and in knowing this, we have a better understanding of why our images often do not come out the way we ‘saw’ them at the point of capture.

Artist proofs available (until Monday 3rd May)

Last year, as part of the preparation for printing my Hálendi book, I had to print out all of the images for verification, and fine-tuning for book reproduction.

I am now selling these off, but I have decided that this should be a limited time offer until Monday the 3rd of May, at which point they will be removed from the site.

The prints are £150 each, and shipping is FREE. If you buy more than one print then there is a further 10% discount.

If you’d like to browse, then press the button below.

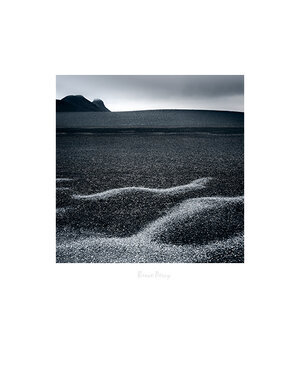

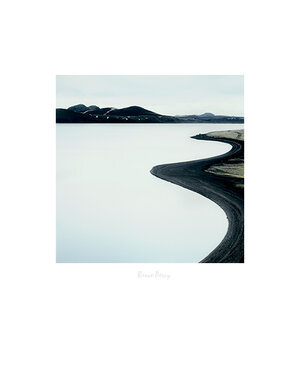

Two views of a valley

It’s my view that trusting one’s initial emotional response to a scene can have two possible outcomes;

1) a strong idea

or

2) a derivative one

And I believe that at the point of capture, we often don’t know which one it is.

To put it another way, while making photos, it is impossible to be an editor. It is impossible be able to successfully judge what we are doing, while we are doing it. The judgement and review of what we are capturing should therefore come much later.

So my view is: just because I’ve found a composition that I like, I cannot trust my judgement that it is the best one available. Although I may believe it to be the strongest composition I’ve found, I have often found that there is usually something much stronger, if I keep looking.

So these days, I tend to make variations of the same shot. Each with some kind of alteration. Whether it’s moving forward slightly, changing the proportions of sky to ground, using a different focal length, or just focussing on a different region of the same scene, as can be seen in the examples in this post today.

I therefore believe that we have one task at hand while we are shooting. We are content gatherers. We are there to collect material to work with later on.

This may sound rather heartless to you, and may suggest that we’re just there to collect raw stuff to make sense out of later on. I do not mean this at all. I simply mean we need to consider all options while we are on location because often the best shot isn’t the obvious one.

Each time I fire my shutter, I put 100% commitment behind it. I am thinking ‘this is perhaps the best frame yet’. But I am also thinking ‘there may be something better if I reconsider the scene a bit more’. I am therefore making insurance shots. I understand that I am in no position to judge what I’ve got, so I better keep on looking in case there is something better.

Judgement of what I’ve captured should come much later, when I am ready to edit the work.

And so if we go back to my initial statement:

It’s my view that trusting one’s initial emotional response to a scene can have two possible outcomes;

1) a strong idea

or

2) a derivative one

And I believe that at the point of capture, we often don’t know which one it is.

And so, it’s hard. Hard to judge whether what we are reacting to is a strong idea, or a derivative one. Once we get past this worry and decide that this is a question for much later, we open up ourselves to what is in front of us, and we become more immersed in the act of creating images.

Looking back, to look forward

In an attempt to find a wider audience, I’ve been experimenting with Instagram this past year (more on this further down).

So tonight I posted this ‘oldie’ on Instagram:

With the following text:

My first 'memorable' image for me, of the Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia. 2009.

Taken more than a decade ago (phew, am I really saying that?), on my first venture to Bolivia, I got a private tour with a Bolivian friend in a Landcruiser. We camped for a night on Pescado Island in the middle of the salt flat (amazing experience), and on a rare cloudy day I shot this.

Originally a 6x7 transparency, I now prefer it as a square. It was an epiphany of sorts for me. A moment where I thought I was onto something, and now, looking back, I see it was showing me the next 10 years of my photography.

Fuji Velvia RVP50 film on a Mamiya 7II camera. I still use Velvia exclusively for all my landscape work (because I know it so well), but the Mamiya 7II's have been replaced in the last 8 years by Hasselblad because I find the square aspect ratio more contemporary.

—

How do I feel about Instagram?

I am grateful for all the lovely comments people leave me. Thank you. For sure. It’s nice.

I also have to thank a lot of friends, and workshop participants that are there to encourage and support me. I know they’re doing it and I appreciate the kindness. It’s very touching. Thank you.

But on the negative side, I am finding that anyone who ‘finds’ me on Instagram, doesn’t investigate further. They don’t come to the website, and they don’t know much more about me. I just become a fleeting memory for most, as they scan past my images. Like Facebook (who own Instagram), they do not encourage visitors to go and explore other sites. For instance, I only have one tiny line at the top of my page to link back to my website and from what I have noticed - few click on this.

I have also been dismayed to find comments that more or less say this:

“I’m so glad you are on instagram, as it saves me from having to go to your website”.

So it’s been a bit of a mixed bag.

But I have not been a fan of social media for a long time. There is something wrong with a mechanism whereby they profit of you giving your data or imagery for free. If you’re not sure what I am talking about then I would recommend you look up Jaron Lanier and his book: Ten Arguments for deleting your social media account right now”.

More on this later.

But suffice to say: thank you to those who have supported me, and who have left encouraging and beautiful comments on my instagram account. I am very grateful. I just think this is the worst place ever to help an artist promote themselves.

Your data is a valuable commodity. Your data is valuable. Without your data, Facebook and Instagram could not function, could not profit. And as social networking platforms, they restrict you from reaching the people that matter to you. They are a brokerage firm, a middle-man who gets in the way of you and your audience. And I think many people are misguided in thinking that they have to be on these platforms to survive. You don’t.

Finding Simplicity in the Complexity

To me, I have always thought that portfolio making is like working on a puzzle, like a jigsaw. It is the skill in finding simplicity in the complexity.

Editing images individually is fine, and that is pretty much how I begin all my images. To a point. But once I start to collate the images into a body of work, I start to see relationships, themes emerge, that influence and instruct me in how to proceed with new edits, or to go back to existing edits to re-tune.

In a week’s time I will begin my portfolio development class. Over the space of four weekly sessions, you will see a condensed version of all the decisions I make whilst editing my work to sit together as a cohesive body.

I thought, how best to teach putting a portfolio together? And the answer came one day on a telephone call with a friend when she asked me ‘have you edited any of your work from that Bolivia trip we did in 2019?’. A light-bulb moment. I realised the best way to convey what I go through whilst editing, is to record myself as I put a portfolio together.

In the video series I’m about to publish, the work was unedited as I started out. I did not know how the work would end up, and this in my view was an ideal situation. Because I wanted the process to be as honest as possible. To show all the trials and tribulations, all the decisions I made, where I got stuck, and where I got set free again to continue.

I am hoping it will be very instructive to those who’ve signed up, as I spare no difficult decision. You see me thrive and also falter at times as I reach difficult decisions in how best to make the work sit together.

Bryan Timmons

This is a message to one of my clients - Bryan from Australia.

Bryan, if you’re reading this….

Your email provider is saying your email does not exist. I get a bounce back each time I try to contact you. Please can you get in touch? Either by phone or another email address?

Bruce.

I see a dragon's eye

On my instagram account, someone commented “I see a dragon’s eye”.

Do you see it?

I have lived with this image for four years and until the viewer commented about it, I had never spotted it.

A plague of virtue

12 minutes well spent.

Stories from South Korea

My good friend Kidoo is my only South Korean workshop participant. He found out about me through a mutual acquaintance while he was on an Iceland tour. Since around 2015, we have been good friends.

Back in 2018, Kidoo suggested I come out to South Korea, which is what I did around December. It was bitterly cold in Seoul, but there was no snow. My first impressions of South Korea was of how urbanised the entire country appears to be. We drove for many hours to reach the coast line and in that time, I hardly saw any nature.

We were together for around nine days, and over that time, I found it very very hard work to find anything that I wanted to shoot, and although Kidoo kept apologising, I kept telling him ‘there must be something there because I’ve shot around 18 rolls of film’. I never shoot unless I really think it’s of some kind of merit, and I’ve been on many trips where I shot zero. So I was definitely of the opinion that something was in the films.

I remember when I got home and looked at the completed edited work. I thought ‘these are really nice, better than anticipated’ and even Kidoo was surprised at how good they turned out. It has always been a reminder to me that work can sometimes progress in small, almost imperceptible amounts. You can be fooled into thinking you’re recording nothing, only to find out later that there is indeed a story that will surface, once you have time to curate and edit.

The funniest memory I have of my brief time in South Koreas, was when we reached some very remote landscape. A real boondocks place, very rural, no tourism, and Kidoo said to me ‘you may be the 2nd European photographer to ever visit here’. The first being Michael Kenna, as Michael has photographed South Korea quite extensively.

A few minutes later we spied an old lady in her 70’s with a Hasselblad medium format film camera. She was South Korean and a big film fan. Her first question to both of us was ‘Have you heard of Michael Kenna?’