But I also recognise something else.

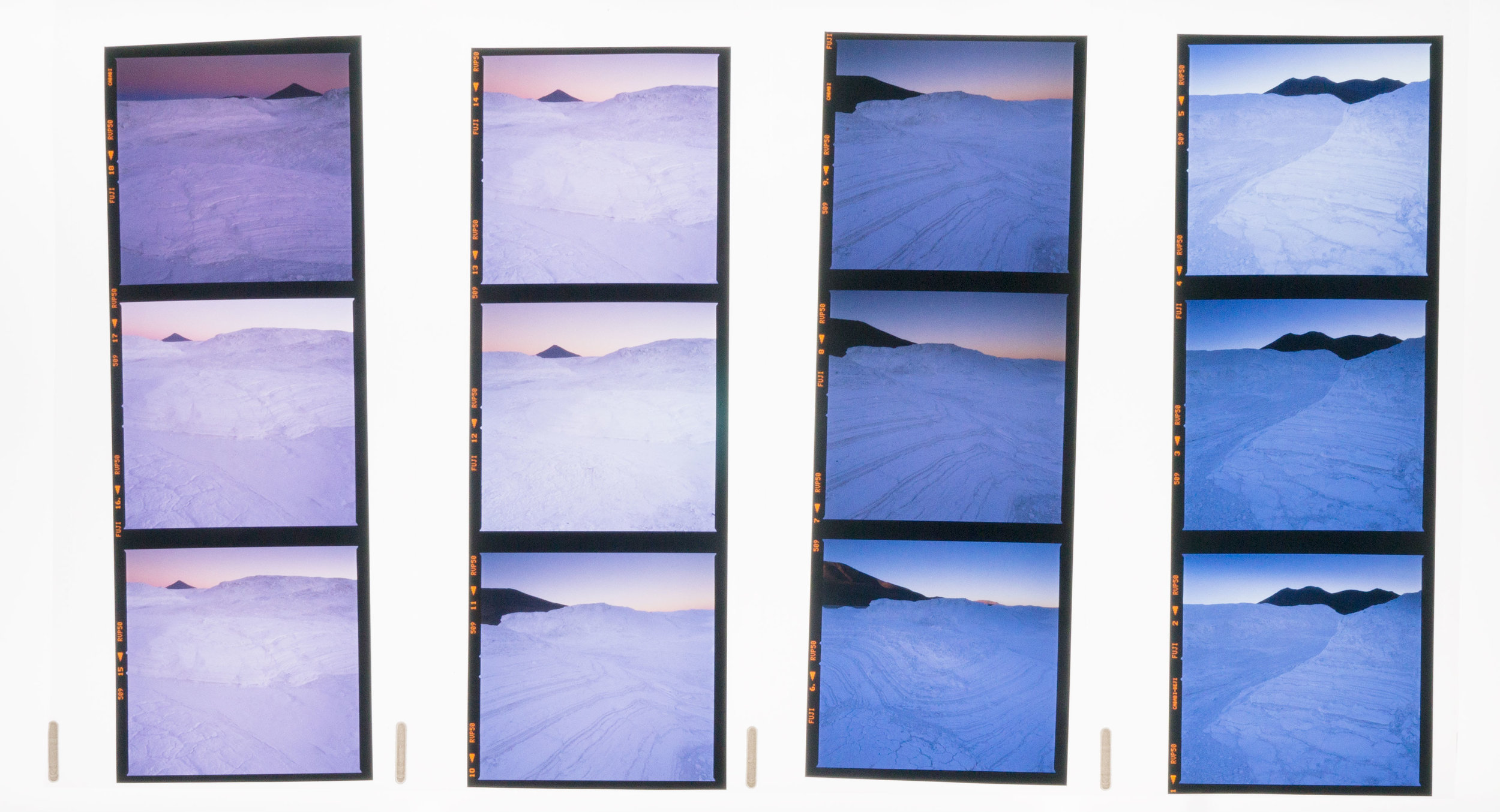

As we gain experience in what we do, we tend to iron out the rough edges. Aspects of who we were are removed and although we may be wishing to improve our technique and vision, I do think something is always lost along the way of progress. Perhaps it's a sense of innocence in that I'm referring to.

I like to think that experience is a double-edged sword. On the one had it allows us to have a better understanding of what can and cannot be achieved, but it can also be a prison sentence. When you know what should be done you tend to discard possibilities for exploration and are less likely to be open to new discoveries: if you don't know there are any rules, you're more likely to break them.

Developing style and perfecting what you do, as much as they are things to aspire to, can become a set of hand-cuffs. As we develop our style and vision, I think we can become less able to experiment. Rather than letting our creativity go in places we have never been before, we may find ourselves going down the same tired old routes because we know they work and there is safety in these familiar patterns.

I think good artists are willing to not only explore, but perhaps more importantly, they are willing to let go of things they know have worked well for them in the past.

It's ok to change. It's ok to say goodbye to aspects of what you did that you loved, or still love. The last thing you need is to find yourself in a rut because you are too afraid to let go of things you know still work well.

To me this is similar to someone who is in a good job, a lovely home, but they wish to go do something else. It's safe to stay where you are because it's comfortable, but there's also something extremely boring and damaging about doing so. All you know is, changing and moving forward although risky, makes you feel more alive.

Looking back at my older work, I see things in it I wish I still had. I'm aware that I've lost things along the way. I do admit to feeling a sense of loss for the qualities I feel I no longer possess, but only in the way that I realise they can't exist alongside where I am now. To change means you have to let go, and when you change anything, you always lose something in the process. It is impossible to have both.

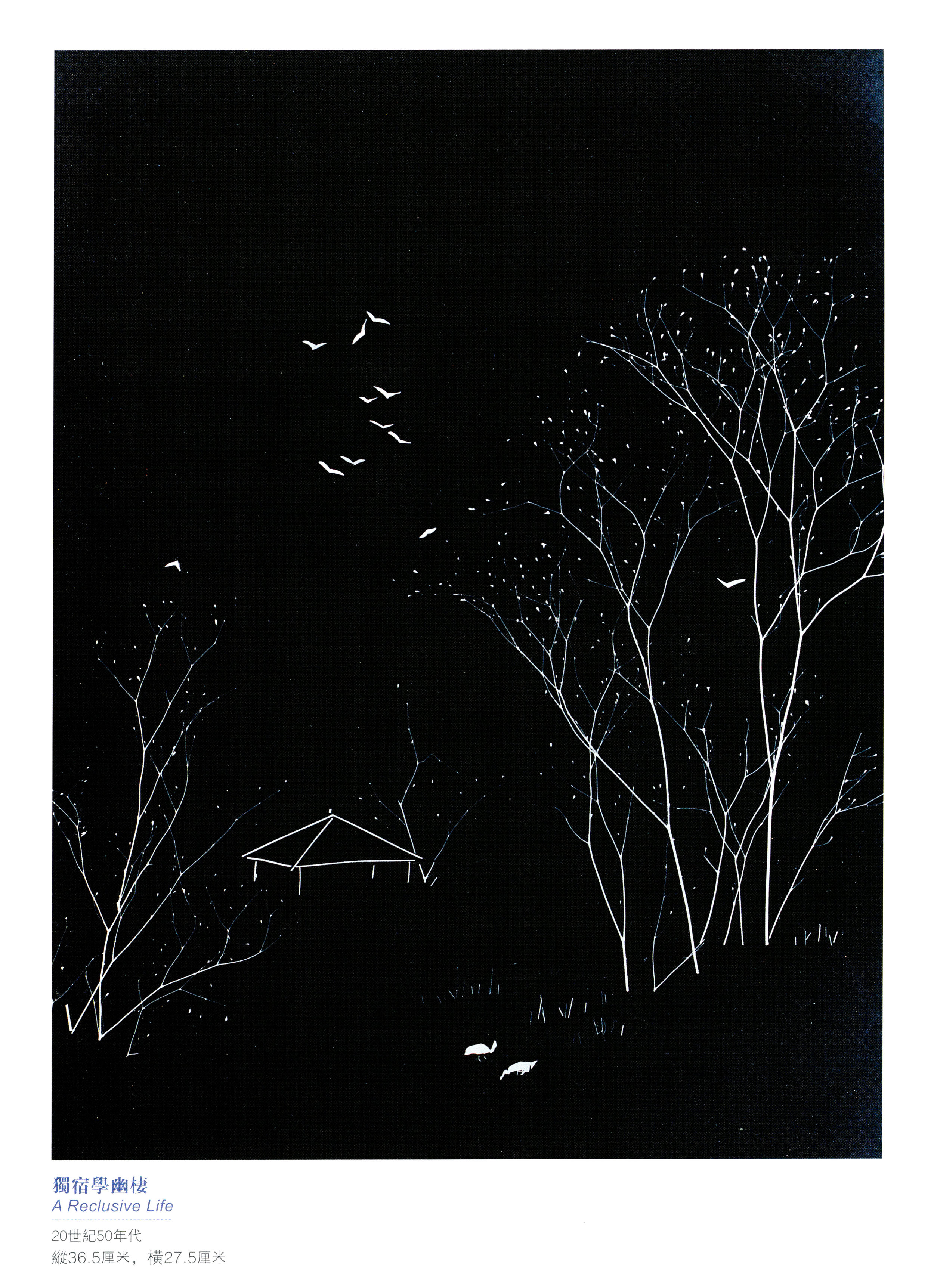

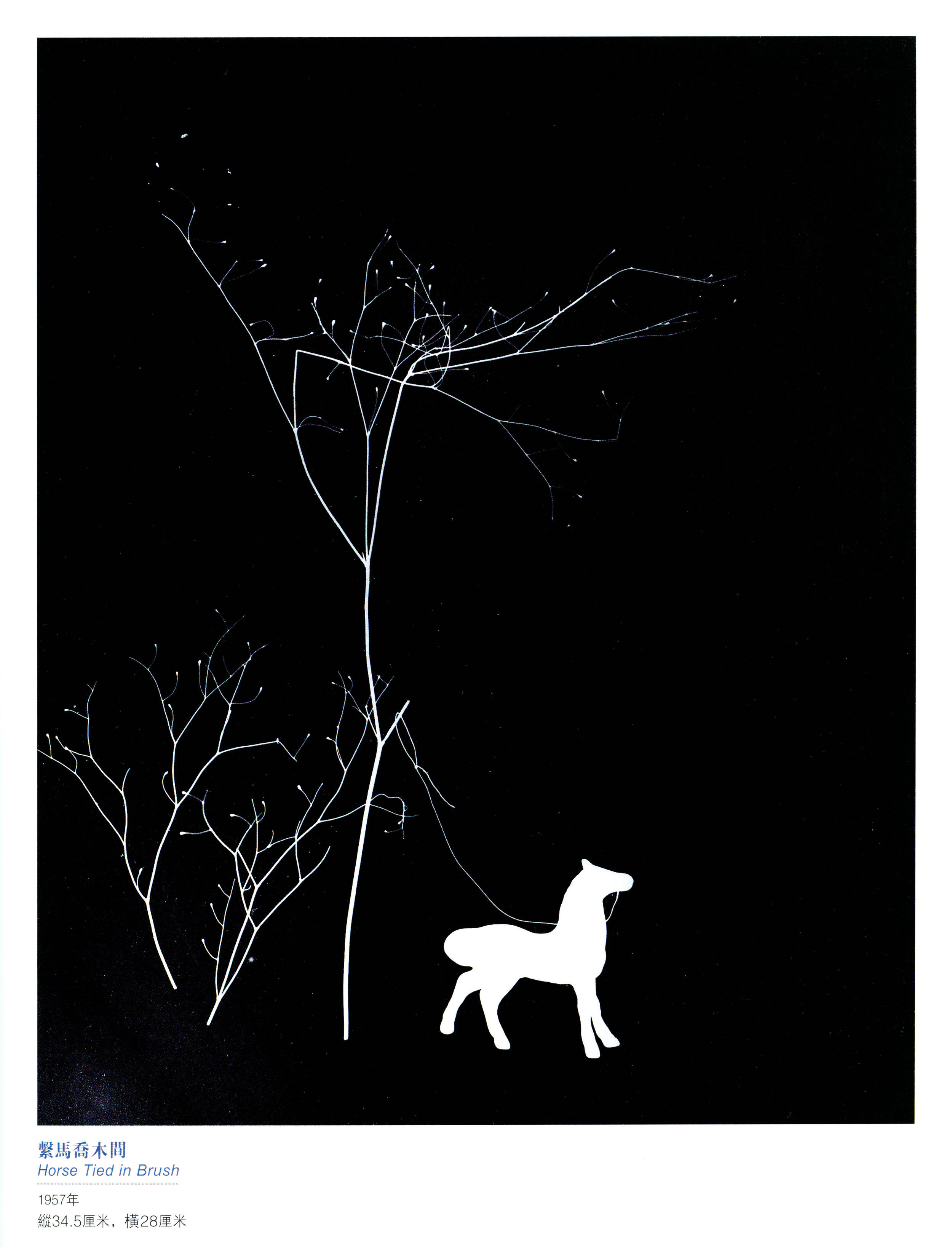

One last thing today before I go. I do think there is something often quite beautiful about early beginnings. This innocence I speak of: this quality of trying out things that somehow become lost along the way: it's an elusive quality. I often see it in many artists work, not just photographers. Musicians and painters, writers and actors. You don't often know you have it when you do, and you don't have it any longer once you know you had it.

It's impossible to recapture the past. All you can do, is keep moving forward and respect where you've come from. Realise it had its time, and that you are different now.