Preamble: this post was originally posted in January 2020. I am going through some of my older posts, as I think many, several years after writing them, are still relevant. I hope you think so too :-)

I am in Hokkaido this month and I’ve been reminiscing about some of the images I have made over the past few years here, and one in particular required me to be high above the ground to accomplish what I saw in my mind’s eye.

This photo was made by being perched up high. While at ground level, I could see that the collection of trees in the bottom of the frame were clashing / hitting the row of trees at the top of the frame. To get the separation between them in my photograph, I had to go this height:

This is the actual photograph of me making the image you see in this post.

Camera height is often a critical part of composition. OK, my example to illustrate that is perhaps extreme, but I have had many times when I have wished to take photos from much higher than my tripod can reach to.

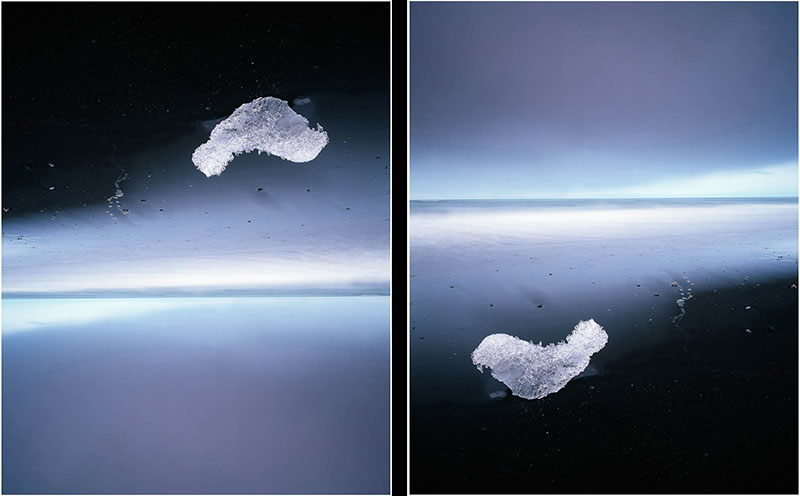

I have also had times when I have wished to take photos that are much lower than my tripod can compress down to. Going low allows me to compress the mid-ground, and it is also a useful device in removing any clutter or debris that is lying around on the ground. Going low also allows me to move objects that are on the ground closer to those objects higher in the frame. By bringing them together / closer, we can strengthen relationships between them.

Tripods don’t find compositions. They fine-tune them

I think camera height is an important consideration for composition. But I am always surprised to see many photographers doing this:

Get out of the car

Extend the tripod to eye-level

Put the camera on the tripod

All of this, without really considering if the height of the tripod is correct for any possible composition they see.

For me, this is what should happen:

Get out of the car

Take the camera out of the bag

Walk around with the camera looking for good compositions

When you find a possible candidate for a good composition, try the composition from different heights: down low, mid-height, eye-level, and of course, from above my own eye-level.

Once a nice composition has been found, set up the tripod to assist in keeping the camera in that ‘magic space’ that has just been found. You know - that ‘middle of the air’ place where the composition works.

So for me, having a very tall tripod is really invaluable. I have two tripods. One is over 7 feet tall, while the other is over 9 feet tall. I have used both fully extended many times, and I’ve been grateful to have the extended reach they have.

A word about centre columns

My tripods also have no centre column. For me, these get in the way and prevent me from putting the tripod so low that the camera is almost at ground level. So when I buy a tripod, I always buy one that is very tall, and also has no centre column.

There will also be occasions when you need the camera to be literally sitting on the ground. In these circumstances I take my camera off the tripod and actually sit it on the ground. I sometimes have to make a hollow in the earth to help support the camera to place it where I need to. But I also need to use a viewfinder that allows me to compose comfortably. For me, I have a 45º angle viewfinder on my camera. For you, you can either use your live-view, or buy a 90º angle finder for your camera (Nikon and Canon).

Tip: when working with cameras lower than you are : get low. That means having to lie on your tummy. You need your eye to be level with the view you’re seeing so you can balance it properly. Peering into a camera with your head sideways isn’t going to help.

Camera height is a critical part of composition. I have found many times that the same composition taken at different heights will have a ‘sweet spot’ where the height is just right for the composition to really gel.