I’ve been wondering how much of my relationship with the landscape has been shaped by my roots? I would say these days that I’m immensely proud of my Scottish background, and feel that the atmospheres, the weather, and growing up in a sometimes ‘dark land’ has had a profound influence on what I’m drawn to.

It may come as a surprise that I think this, because I haven’t really made any serious effort to photograph Scotland in well over a decade now. But I would like to point out that I think I have been chasing the spirit of the Scottish landscape elsewhere.

Let me explain if I can: you have to leave sometimes, in order to return, because there is a lot to be learned in the parting, and similarly, a lot to be learned in the returning.

In all relationships, parting for a while has a lot to teach us about how we feel about the relationship. Having time apart allows one to gain objectivity about what is important in the relationship. Coming back is always the time when we know just how we really feel about the relationship.

So that is how I feel about Scotland. I spent the first decade of my photographic life making all my photographs here. But I didn’t think I had enough objectivity to really appreciate the landscape. It was my ‘norm’, and as all ‘norm’s go, you can’t see them for what they are if you are staring at them all the time.

I have found that as I’ve continued to travel abroad, it provided context, and contrast. Going somewhere quite different from what you know, makes one realise just how special or unique a familiar landscape can be. But I also think that going somewhere quite different allows one to notice similarities as well.

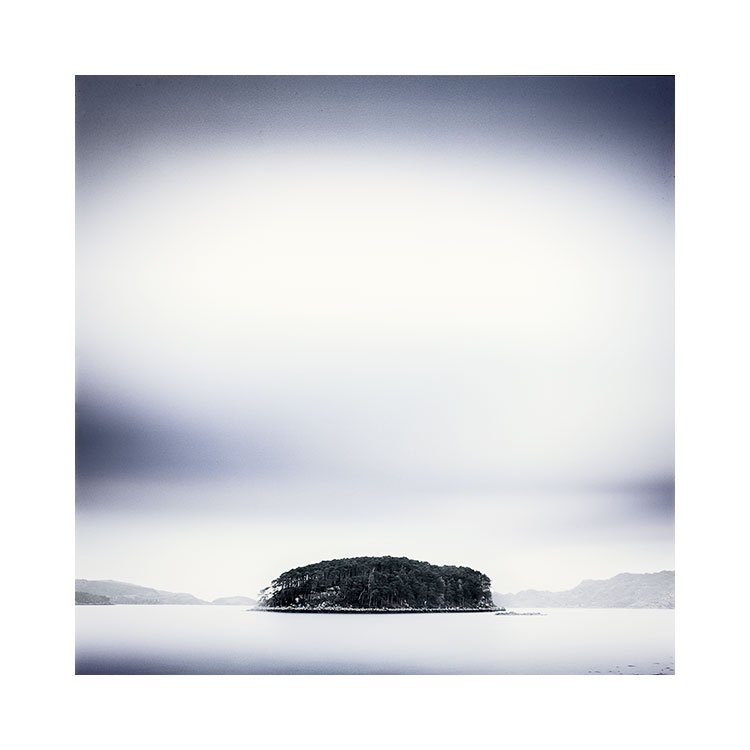

Particularly the similarities. They seem to indicate to me that I’ve been ‘chasing Scotland’ elsewhere. I seem to be drawn typically to landscapes that have a lot in common, at least weather wise, and perhaps tonally as well.

I haven't done much travelling for obvious reasons for around 20 months now, and I’ve found this has been a form of ‘returning’. As I’ve started to reconnect with my homeland, I’ve come to acknowledge that my past, my upbringing, and living in a Scottish climate has had massive impact on what I’m drawn to.

Last December I lost my dad. I was very close to him, and we had a terrific relationship where he often told me that we were more like buddies than father and son. He was a highlander. From Sutherland with that Highland lilt and clear pronunciation of accent. As the months since his death have progressed, I’ve found myself reflecting about our time together, and how in fact, every thing we experience is transitory, and to be cherished. I think that a parent’s death is a rite of passage for many of us. It brings on time for reflection, for understanding who we are, and where we are in life. And I found myself realising that this awareness of my Scottish roots has been surfacing for some time. As is evident in my foreword to Julian’s book.

In the foreword, I wrote about my childhood. And although it is not explicitly stated, I was describing Glencoe. I have very strong memories of how Glencoe was this foreboding landscape that I didn’t know the name of, but was so memorable because it had a mood and an atmosphere like no other.

I know my family holidays into the highlands shaped me. I know that when I go to Patagonia or Iceland, I am working with what Scotland taught me about mood and character. The Scottish landscape, it seems, has been at the basis of everything I’ve been shooting in one way or another. Except I have only been able to realise this by reflecting upon my time with my dad, my childhood, and of course, by spending time apart from it.