Yesterday I reposted an old blog entry about viewing images upside down. The main benefit of looking at your photographs upside down is that it forces your eye into areas of the frame that you rarely visit.

You see, I have found that we all have a predisposition to walking through the frame a certain way. In my own case, I often walk through an image from left to right, but depending on the compositional content of the picture I will either start from bottom-left and end up at the top-right, or I’ll start at the top-left and end at the bottom-right.

Left to right walking

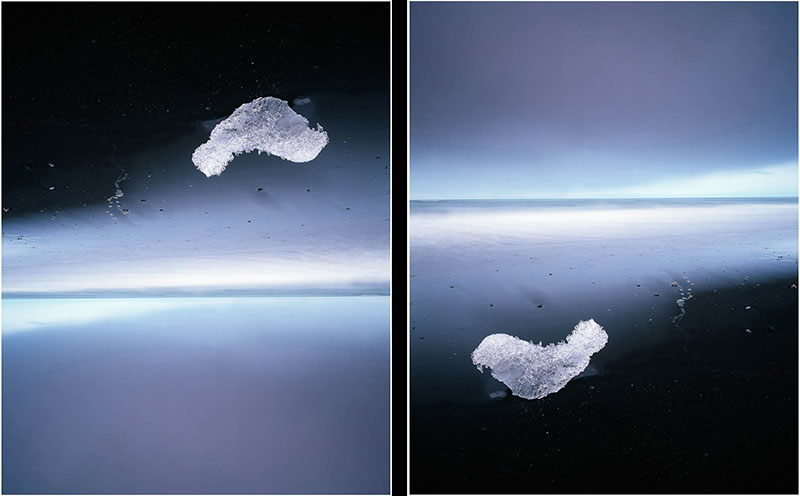

Red marks the areas where you may be blind if you tend towards scanning images from left to right.

Left image: left-to-right scanning from bottom to top.

Right image: left-to-right scanning from top to bottom.

In each ‘walk’ described above, I essentially ‘blank out’ the red regions of the image. In other words, if I walk from bottom-left to top-right, I spend very little time in the top-left and bottom right areas of the picture (see diagrams for a clearer illustration of this).

Until I turn them upside down that is.

That’s when I find that my eye is now forced to roam into regions of the image that I didn’t when I first walked through it.

Right to Left walking

Red marks the areas where you may be blind if you tend towards scanning images from right to left.

Left image: right-to-left scanning from bottom to top.

Right image: right-to-left scanning from top to bottom.

Over the years I have been teaching workshops I have found that out of a group of six participants, two-thirds of them follow the same flow that I have whilst walking through an image. They start bottom left and end top-right, or if the subject demands it they start top-left and finish bottom-right.

With my ‘theory’ in mind,

how does your image tend to scan the image above,

when it is the right way up, and when it’s rotated 180º?

Blind Spots?

I’ve come to the conclusion that regardless of whether my ‘theory is correct’, we all have visual blind spots when we look at an image. It may be due to how the composition is constructed, but the fact is that we spend more time in certain areas of the image than other areas, and those areas we don’t spend time in - are areas we often don’t visit.

This is a handicap of sorts. Because it means that we are visually blind to certain areas of the frame. This can affect us whilst outside composing our photographs and also while editing them.

So yesterday, I suggested that if it’s at all possible to review your images upside down, you should do so. It’s simply because our eyes tend to walk through an image a certain way, blanking out regions of the photograph that may be problematic to other viewers. By turning the image upside down, your eye is forced to enter into regions of the image it wouldn’t have done if it were the right way up. And by doing that, you are forced to notice things about the image that you were originally blind to.

You are effectively seeing the image anew, and you are being forced to confront areas of the picture that you were perhaps weak at working with at the time of capture.

We are all visually blind. I like to think that photography is the pursuit of learning to see again - of noticing the things we have a tendency to pass over. Turning images upside down can aid you in working around your visual blind spot.

Try it for yourself

With all of this in mind, try it with your own images. Ones you are happy with, and ones you are not so happy with. You can learn so much by rotating them. Do you notice things you didn’t see before? If you do, then think about why that is. Perhaps you have some blind spots when you walk through an image.