I’ve just spent some time over the past week curating the images on my website. To me, my website is like a garden of images. A space in which to let things grow over time.

I have just re-introduced a few portfolios that I couldn’t find space for. There are a few reasons why I take some of the portfolios off-line for a while, but mainly it is due to layout concerns:

1) I may have a portfolio that does not fit with the rest, maybe due to the tonal palette or subject matter.

2) I may have too many portfolios of the same region shot over many years, and in order to give the site some kind of clarity, will remove portfolios which I feel aren’t necessary to convey where my style is going.

3) I think my website is also a place where you can see the adaption or change in my style over time.

4) I am maybe unsatisfied with some of the work, so it gets shelved. Over the years, I have found it increasingly difficult to keep my older work on the site, because it feels too far removed from where I am now. Or I am now quite embarrassed by the work (which in my view is an indication of growth).

I thought it would be good to show the new sections of the site, and perhaps describe how I have chosen to lay them out.

The page above is my most recent work. As a beginner photographer I am convinced I would have considered this work to have no colour whatsoever. But just for comparison, I show you the images below converted to black and white. You can now see that there is indeed colour in the work above. But I am sure for many they may perceive it as having none.

It’s interesting to find that looking at my older work from eight years ago and beyond, the colours feel too strong, too obvious and the older work speaks of trying too hard. It is my own view that muted colour comes from an understanding that you don’t need to shout to get your point across. I’d of course love to think that it comes from a place of maturity (hee hee hee), but I do wonder in all seriousness, that once you get past the need to impress others with your work, you settle into a place where you are comfortable doing what you do, and feel that you’ve figured out just how much contrast and colour is required to make your point.

I’d like to point out that none of this has been done with any premeditated intent. It’s just been an evolution of sorts and I’m never too clear as to whether this is just a case that my tastes have changed over the years, or whether it’s more a case that I’m seeing and noticing things more. I’d of course love to think it’s the latter ;-)

In the page above, if I were to look at this in isolation, I’d maybe assume that my work hasn’t changed much since 2017. It’s only when I do a direct comparison with my more recent work that I can see that the more recent work is taking the colour reduction and subject reduction further. A fine-tuning perhaps? (I’d love to think so!)

But you can see there’s still a bit more colour in this collection of image. I think the muting down of colour has been a learned experience for me. Going to the Fjallabak region of Iceland in winter time (bottom right), where there was almost no colour - I was shooting black and white scenes with colour film, I learned so much from this.

I have often said that certain landscapes, if you meet them at the right time in your own photographic development - can move your photography along in leaps and bounds. I am convinced that had I stayed in IT, and never been able to shoot so much, and go to so many of these winter places over the past 10 years, that my style maybe wouldn’t have moved on so much, if at all. I’m convinced that working in the Interior of Iceland, reducing things down to their utmost basic elements, gave me the permission to attempt to do the same with less empty landscapes.

I’m pleased to re-introduce my Romania, Harris and some of the more minimal Fjallabak portfolios. I’d almost forgotten about them :-) But now that I’ve re-introduced them on my site, I think there’s a more completed story of my own progress (for me at least).

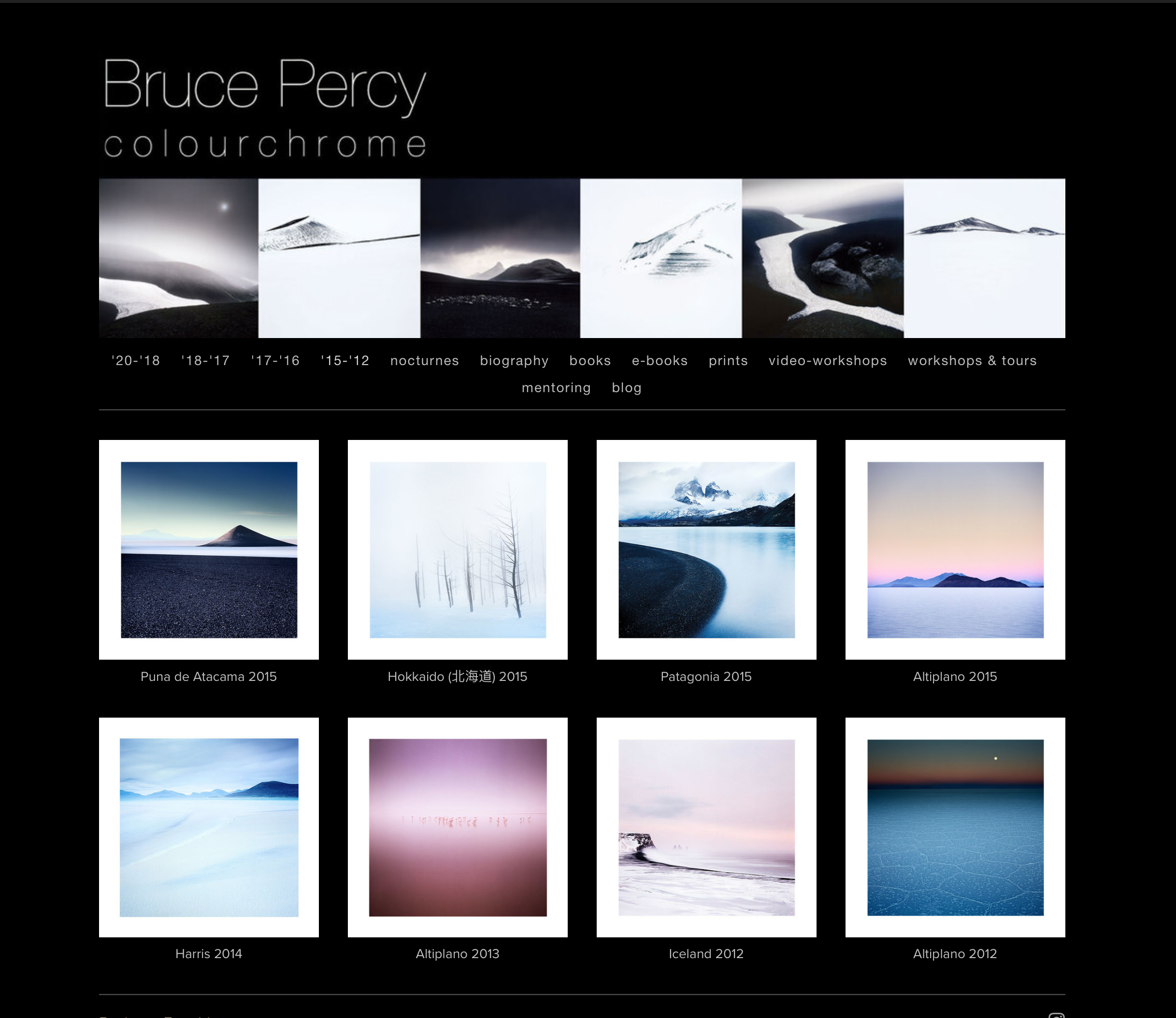

In the page above, you can see there’s a mix of more ‘traditional’ looking landscapes with the graphic elements that I like to play with. At the time of making these, I was thinking that I’d maybe gone as far as I could with simplification. Not that I was consciously trying to strive towards it. Everything I’ve done has been purely emotional, despite others thinking that I deconstruct landscapes. I don’t. I just shoot what appeals to me.

But looking at these, that cone shape in Argentina (top left), taught me so much about the graphic nature of composition. That sometimes shape, is all that’s needed to make a powerful image. I’d certainly say for me, there are a few epiphanies in this collection of work from 2016 to 2017. Working with the Fjallabak region of Iceland allowed me to start to subtract colour, to embrace blacks as negative space. I also find it telling that personally for me, the Altiplano shots here, are not my strongest. I feel that by this point, I had ‘mined’ as much as I could out of the Bolivian altiplano and this was at the tail-end of my work there. I knew my book about Altiplano was almost ready because I was starting to run out of ideas and to see new things in this landscape. I think this is perfectly natural and it either signals that your work in a region has come to an end, or your current level of style and ability can’t go much further in it at present. Perhaps if I return in 10 years time, I may find that I am able to see new things in a old friend?

In the page above, I’ve been able to re-introduce some early work from Iceland’s coastline from 2012, and also some earlier work from the Bolivian altiplano from 2012 (last two portfolios).

By contrasting this page to my more recent work, it’s evident that I’ve been subconsciously on a colour-reduction quest, as well as tonal-distraction-reduction quest also. As I say, none of this was consciously any decision on my part. I just think my style has evolved.

What is interesting to me, is that these images are just on the periphery of what I feel is acceptable to show you. Older work from 2011 back to when I started out - does not work for me at all any more. I find the colours too gaudy and the contrasts too hard, and I feel that in my much older work there was a need to get my point across, perhaps too much.

I do feel that all the landscapes I’ve shot over the years have been great teachers. There are many places that I went to that never amounted to anything (Yosemite valley springs to mind) where I could do nothing with the subject matter, or where I found the location too hard, too difficult to work with (I still think Scotland is like that - there is just too much chaos in the landscape, too much tonal distractions for example). I tend to go back to landscapes that allow me to grow and I think I’m good at figuring out when a landscape allows me to do that.

I have often said that many photographers try to shoot landscapes that are too difficult for their current level of ability. It is much better to focus on the landscapes where you feel you are getting somewhere with. I am convinced that they are growing places for you. It is my view therefore that returning to a key number of places over the years, as I have done, allows for more intimate study and growth of one’s own style. The subject matter to a degree informs the style, and the style to a degree informs what you choose to shoot.

As I said at the beginning of this post today, I look at my website as a garden. I am often able to see where my style has evolved over time, and also how my images in certain landscapes have changed over the years.