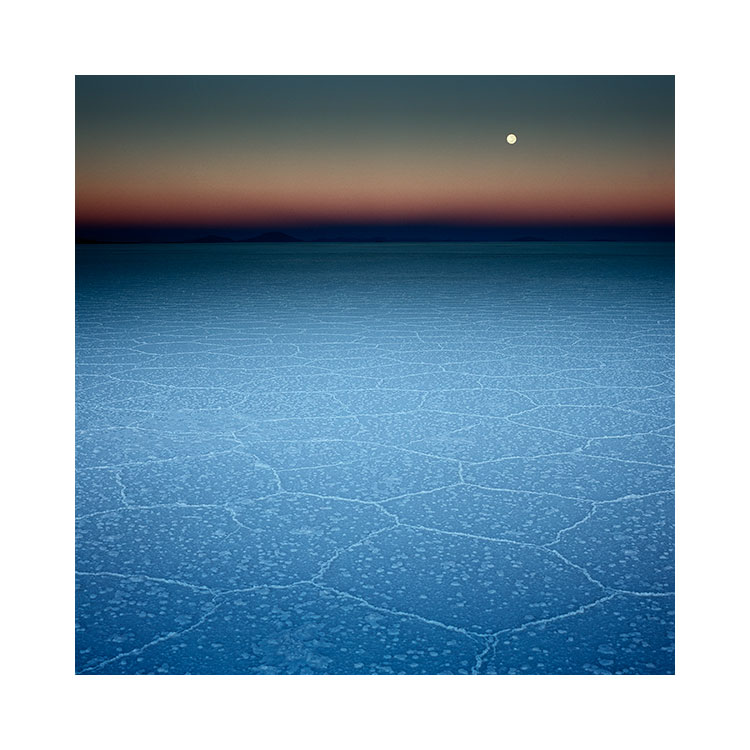

In a short while, I will be announcing a new book about the south American atacama. The book encompasses photographs from the Argentine, Bolivian and Chilean high plateau. It has been a work in progress for around 8 years.

I had the 'working title' for this book earmarked around six years ago. I find titles a great way to conceptualise and to think about which way to steer my creativity. Once I had the title 'altiplano', I felt I knew what should be in the book, but also perhaps more importantly - what shouldn't.

The proposed title for my future central highlands of Iceland book. I hope to publish this in the next year or two.

I find projects or themes a great way to steer myself forward. My creativity is more focussed once I have the 'correct' theme in mind. But the theme doesn't always surface straight away and I find that 'working titles' can morph into something else if I live with them for some time. 'Working titles' are like clothing: you try them on for size and to see how they feel. You need to wear them for a while to see if you grow into them or to find that they really don't suit at all.

Altiplano was one title that stuck from the moment I had it. It made me realise that I couldn't add in other landscapes from around Bolivia - I had considered the mines and some other areas but they weren't part of the region that is defined the altiplano. Boundaries are important in focussing attention.

I don't know if I've discussed this on this blog before, but my graphic designer friend Darren and I have been playing around with themes and designs for a set of books. The first of which is coming out soon. We pretty much hope to publish a further two books over the next few years.

I'm hoping to publish one about the central highlands of Iceland - this will be a book with no 'popular' landscapes in it. No classic waterfall shots, etc. It's all about the remote interior, and I hope for it to include my images from my winter shoots in the interior, and also the dark landscapes I encounter throughout the rest of the year.

The proposed title for my Hokkaido book.

The other is about Hokkaido. You can see 'mockup's' above. I wouldn't take the designs or titles too seriously right now - I'm showing you these to illustrate the process I go through - these are just 'working titles'. Hálendi means 'Highlands', and Shiro means 'white'. Just working titles and it's too soon to say whether they will stick.

What these working titles give me, is a way of visualising the final books. I've already been collating the work from each landscape, and I've managed to choose around 50+ images so far. But I can already see gaps in the work - areas where I need to look for images to fill out areas of the landscape that I have either missed out on at times in the past, or that I know are still there to be photographed.

Working titles are a great tool to help steer you forward. Making individual photographs isn't enough. If you find yourself feeling rudderless, not sure where to go with your photography, but at the same time know that you are creating good individual images, then I would suggest you need a concept: something to help you glue your work together.

The whole is always greater than its parts, if you get a really strong theme or 'working title'. It can propel you and give your creativity focus.