I use many kinds of colour neutral filters in my work: ND-grads are used to control the contrasts between sky and ground, and I also use Full-ND (neutral density - i.e no colour filtration - just darker) filters in my work to control the shutter speeds so I can get the effects I'm looking for, regardless of what the light levels are at.

For a long while I've used the Lee filter system. I've found the system to be one of the best out there, and for most things I've been very happy. The filter holder is well designed (unlike some of the other brands I could mention) and the filters - especially the grads are all hand made. I've also found that compared to other brands, they are less prone to introducing colour casts when compounded together. With most other filters I've tried, I find that combining a 3-stop full-ND filter along with a 3-stop ND-grad filter can introduce a very obvious magenta colour cast in the final images. With the Lee filter system, the colour cast isn't completely gone, but it's certainly the least pronounced and most of the time I am happy with being able to tune it out later on.

One of the filters I don't use by Lee, is the Big Stopper. The main reason being that I seldom require 10-stops of ND for what I do. This is because I am a film shooter who finds that during low light photography the reciprocity effects on my film mean I'm into long shutter speeds without needing to add anything more than a 3-stop Full-ND filter. For example, Fuji Velvia becomes less sensitive after 4s. An exposure of 4s with a 3-stop Full-ND filter applied becomes 32s. Once I apply reciprocity to this (the film loses it's sensitivity the longer its exposed, so I need to compensate for this by adding more exposure time) the exposure is already down to 1m 6 s.

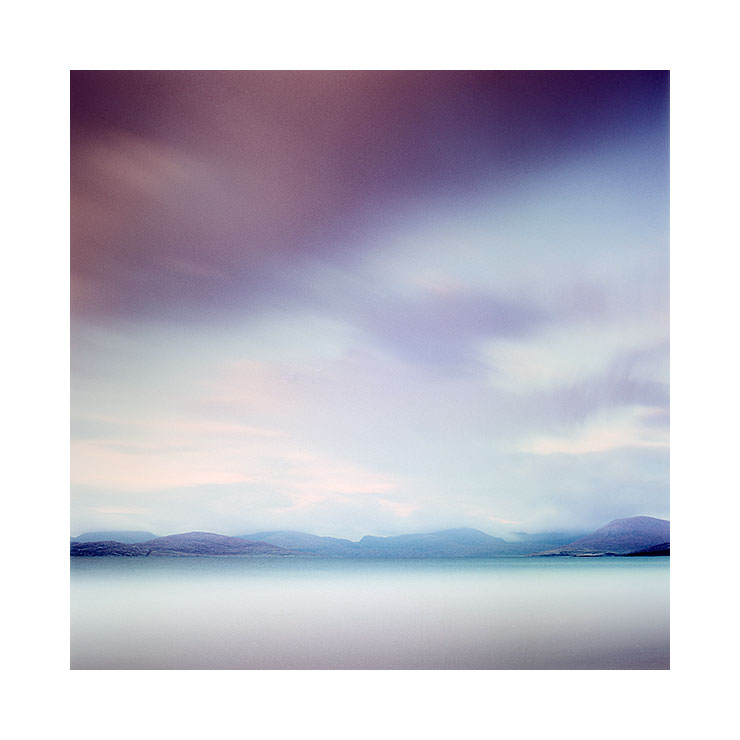

So a Big Stopper has never been needed, or wanted for what I do. But I do however use 6 stops of Full-ND from time to time, and that means compounding 2 x 3 stop Full-ND filters along with a 3 stop ND-grad. Which often means I'm introducing a real magenta cast into the image - which is uneven - it's very pronounced in the sky and less so in the ground, but it's still there. I've avoided using the Lee Little Stopper, because it has the same very pronounced blue cast that is evident in the Lee Big Stopper.

So I was interested when I heard this year about the Firecrest Full-ND filters from HiTech (thanks Jeff for making me aware of them). I decided to buy two filters from them: one 3-stop NFull-ND filter and one 6-stop Full-ND filter. Now that I have images back from the shoots I used them on, I'd like to discuss their neutrality and also their physical attributes in today's post.

Colour Neutrality

They are completely colour neutral. Phew, it took me a while to get to this point, but there you are. Worth every penny and a remarkable technological step forward.

Filter physical build and thickness

This is a description from the Hitech website:

"Rather than dyed resin, Firecrest is a carbon metallic coating used to create hyper neutral NDs. The filters are made from 2mm thick Schott Superwite glass, and the multicoating is bonded in the middle to increase scratch resistance. Firecrest Filters are neutral across all spectrums, including UV, visible, and infrared."

The Firecrest filters a slightly slimmer than the Lee's, so there's been some discussion that they may fall through the Lee filter holder. I've found that the filters are indeed a little bit slimmer, but I've not had any worry about them falling through. I would say however, that it's dependent on the age of your Lee filter holder. I find over time that the little rubber parts that hold the filters in place tend to get loose or soft. So it might be worth checking this out before using the Firecrest filters in your Lee holder. I think the fix for a loose filter holder is simply to buy some new spacers for it, or a new holder (I've always got a spare one anyway).

Glass Filters and Fragility

The last concern for me about using any glass filter is its fragility. It's well documented that the Lee Big and Little stoppers may break just being stowed away in a normal camera filter bag. So for the past several years they've been released with little metal cases to avoid the chance of this.

With the Firecrest filters, they come in rather large plastic cases. Too big in my opinion for storing in most camera bags, so if I had some recommendation to Hitech - it would be to produce a smaller set of cases please. But maybe this is a moot point, because I chose to see if the filters would break if I put them in my normal filter case. After six weeks of traveling on really rough unsealed roads in Patagonia and the Altiplano of Bolivia, the filters are still intact and I feel confident that they're not too fragile at all (they won't bounce if dropped, but at least they aren't going to break too easily if placed in a normal filter bag).

Summary

If you tend to compound ND-grad filters with Full-ND's a lot, then using the Firecrest Full-ND filters in your mix of filters is definitely the way to go. They will cut down the possibilities of colour casts and allow you to be more free with the combination of grads with Full-ND's you use.

If you use the Lee Big or Little stopper, then I would recommend you replace these filters now with the Hitech Firecrest equivalents. The Big and Little stopper filters have a very pronounced blue cast whereas the Hitech ones are completely neutral. (On a side note - you may feel that you can 'tune out' the blue cast from the Lee's during raw conversion, but please bear in mind that the blue cast may not be uniform across the entire visible spectrum. So I'm not convinced that tuning the colour temperature fixes the issue entirely, and may introduce cross-over casts in other tonal ranges of the image).

For me, since I tend to compound filters (an ND-grad + several Full-ND filters) I've replaced my 3-stop Full-ND filter for one 3-stop ND firecrest filter and I've bought an additional 6-stop Full-ND firecrest filter (to get round those times when I previously used 2 x 3-stop Full-ND's).

I see that Hitech have also released some soft grads in the Firecrest range, which means we now have the possibility to use completely neutral ND-grads as well, but I haven't tested them yet, but have now placed an order for them. So I hope to tell you in a few months time once I've used them a fair bit. Until then I will continue to use the Lee ND-grads as I still maintain that they are the most colour neutral resin filters on the market.

For any full-ND requirements, I will now be using the Hitech Firecrest range with no reservation from now on. I'm delighted with the results :-)