In black and white photography, tinting prints - tritone, duotone, quad tone, is a staple of the process. Black and white often uses hints of colour in the shadows and highlights to give the work a particular feel or look.

But in colour landscape most photographers don’t apply the same principles to their work. When it comes to editing, few consider using colour thematically. By that I mean, few consider using colour to give their work a particular kind of look or feel. Yes, they may saturate the colours or mute them, but that is often as far as it goes.

Adjusting the colour palette, or ‘look’ of a scene has been a staple of the motion picture industry for a very long time. Movies are there to tell stories and to take us into another world. One way that movie producers take us into another world is by the use of colour. They will often adjust the colour palette of a movie to give a certain feel to it. This is called ‘colour grading’.

In colour photography, many of us choose to adjust contrast and overall saturation of colours, but few of us use colour to convey a certain mood of feeling to the work.

Perhaps you feel that adjusting colour in this way is not what photography is about? Perhaps you feel that photography is about recording what was there?

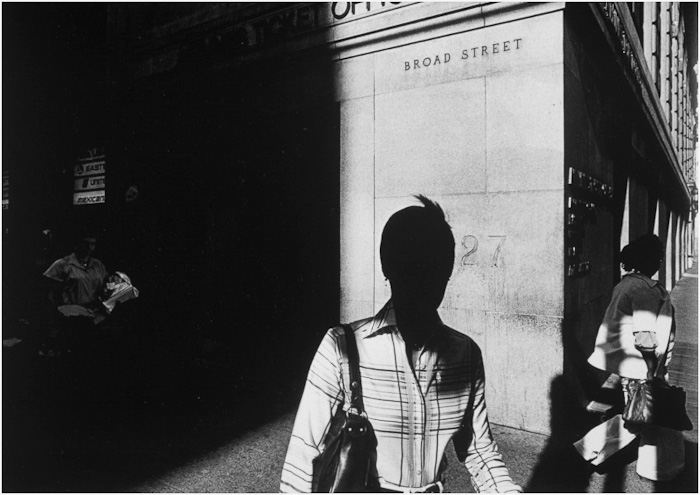

I hope the opposite is true for you. That you like photographs to convey a mood or a feeling, and that you think of photography as a creative medium where you can cast a spell over the viewer. Photographs aren’t real. They never were. Everything about the process introduces a point of view: where you stood to make the shot, what lens you chose, what exposure you opted to give the shot. All these decisions mean that you are telling a particular story. A point of view. An illusion.

One of the most under-utilised tools in our editing process is the choice of colour palette. It’s something I’ve been working with now for about the past five years: I look for photographs that have similar colour palettes to work as a portfolio. Colour and how it is applied, is just as important as where to stand was, or what lens to use. Colour is part of how we tell our stories, and using it in a delicate, considered way to ‘colour grade’ our photographs is a skill that most never consider.

I colour grade my work all the time. I consider the use of colour just as important as all the other more mainstream actions we take. I’m not interested in whether the colour is accurate to what I saw, but more about whether the tonal and colour palettes give me the look and feel I want.